In the arid stretches of rural Kenya, where dust hangs heavy in the air and the sun shows little mercy, a child’s school day often begins not with a textbook, but with a jerry can. For millions of learners, the absence of reliable water in schools is not a minor inconvenience—it is a daily obstacle to education, health, dignity and equality.

As Kenya pushes toward its Vision 2030 ambitions of universal education and sustainable development, the persistent water crisis in schools exposes a troubling disconnect between national aspirations and lived realities. Without safe, sustainable water in learning institutions, we are not merely denying children a drink—we are quietly draining their potential.

The data is stark. Kenya’s WASH in Schools Strategy 2024–2029, jointly developed by the Ministries of Education, Health, and Water, Sanitation and Irrigation, estimates that one in four rural primary schools lacks adequate water facilities. Where infrastructure exists, sustainability is a major challenge: 35% of water systems fail within three years, largely due to poor maintenance, weak ownership and unsuitable design.

Hygiene conditions are worse still. About 85% of rural schools have limited or no handwashing facilities, while half fail to meet basic sanitation standards. These figures, largely confined to rural primary schools, also point to a deeper problem—significant data gaps for urban, peri-urban, secondary and pre-primary institutions, reflecting weak monitoring and accountability.

The consequences are profound and far-reaching. Water scarcity fuels preventable illnesses such as diarrhoea and cholera, driving absenteeism and undermining learning outcomes. A study in Muhoroni Sub-County showed that only 65.4% of learners had access to safe drinking water, a deficit closely linked to poorer academic performance.

Global evidence from the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme reinforces this link, while highlighting how inadequate WASH services disproportionately harm girls. In Kenya, the lack of water and private sanitation during menstruation contributes to missed school days and heightened dropout risks. Encouragingly, targeted WASH interventions have reduced these challenges by over 30% in hundreds of schools, proving that solutions work when properly implemented.

Climate change is compounding the crisis. Recurring droughts have left millions of Kenyans water-stressed, with schools in arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs) bearing the brunt. UNICEF continues to report hundreds of schools with no water source at all, many dependent on unreliable rainwater harvesting. As climate shocks intensify, water access in schools becomes inseparable from resilience, food security and long-term development.

Yet amid the challenge, there are promising examples of what is possible—particularly where the private sector has stepped in to complement strained public resources. The national WASH strategy’s Three-Star Approach offers a practical roadmap, moving schools from basic access to safe, adequate and sustainable services. Community initiatives, donor-funded boreholes and solar-powered systems have made inroads. But one of the most compelling models comes from local financial institutions aligning purpose with impact.

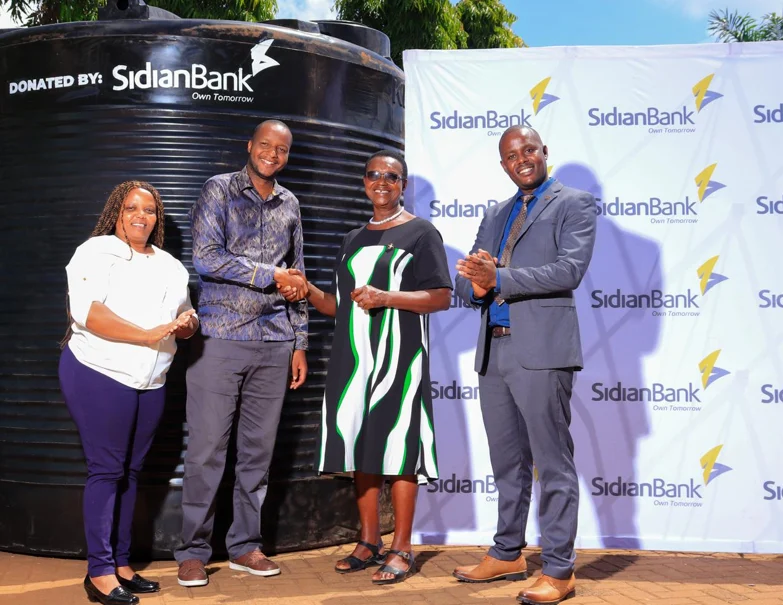

Sidian Bank’s growing footprint in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) illustrates how targeted, locally grounded interventions can deliver real change. In Meru County—long plagued by water scarcity—the bank recently rolled out a WASH campaign donating 10,000-litre water tanks to schools across multiple constituencies. Delivered in partnership with local leaders and community structures, the initiative directly eases daily water shortages in schools while reinforcing hygiene and long-term resilience.

As Simon Mwangi, Head of Government and Institutional Banking at Sidian Bank, noted: “Access to clean water is not just a basic need—it is a foundation for health, dignity and economic stability. Through this WASH campaign, Sidian Bank is investing in practical solutions that respond to real community needs.”

These school-focused efforts sit alongside Sidian Bank’s broader WASH financing innovations. Through partnerships with Oikocredit and Aqua for All, the bank launched a KES 1 billion WASH Loan Facility (2024–2027), targeting more than 480 SMEs and small-scale water service providers with tailored loans, technical assistance and performance-based grants.

Earlier initiatives—including Covid-19 WASH facilities and challenge funds—have reached millions by expanding access to clean water. By prioritising climate-resilient infrastructure, women-led enterprises and sustainable repayment models, such financing indirectly strengthens water access for schools embedded in underserved communities.

Still, these successes remain fragmented without systemic scaling. The national strategy itself identifies persistent barriers: underfunding, weak coordination under devolution, and limited technical capacity at county level. Addressing this demands political will—ring-fenced WASH budgets, stronger integration into education grants, and robust public–private partnerships. Corporate actors like Sidian Bank have shown what is possible, but government leadership must anchor these efforts within a coherent national framework aligned to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 4 (Quality Education).

Water access is not a peripheral issue. It is constitutional, foundational and non-negotiable. As donor support shifts and Kenya’s development financing landscape evolves, domestic institutions must fill the gap with innovation and accountability. Empowering school management committees, health clubs and local leaders—while scaling proven models like Meru’s tank donations and WASH financing—can ensure facilities are not only built, but sustained.

The choice before us is clear. Kenyan schools can remain parched spaces of missed opportunity, or become oases where children learn, thrive and dream. Investing in water is investing in education, equity and the country’s future. The child freed from fetching water during school hours today may well be the innovator quenching tomorrow’s thirst—if we act, decisively, now.

Read: Sidian Bank Rolls Out CSR Initiatives In Meru To Support Access Of Clean Water In Schools

>>> Pwani Oil Targets Water-Scarce Regions With Hygiene Initiative in Kenya

Leave a comment