Banks are now calling for a review of interest rates cap law, saying it has failed to achieve its objectives. According to the Kenya Bankers Association, the push for the amendment of the Banking (Amendment) Act 2016 is based on evidence of market outcomes and bank level data that confirms the adverse consequences of the law one year into its implementation.

The KBA survey covering 77% of the banking industry reveals that the law has exacerbated the decline in bank credit to the private sector, it says, adding that lending to the sector is nearly grinding to a halt, with the most affected being unsecured personal loans.

“Given the demonstrable association between credit growth and performance, the overall economy is adversely affected. In essence, the law is aggravating an already delicate economic performance,” KBA says.

Given the constrained ability of banks to freely price risk under the law, the analysis of the survey findings reveal a heightened scrutiny of loans. As a consequence, a huge discrepancy between the number of loan applications and what was actually disbursed is evident. Since May 2017, it says, loan disbursement has been on a declining trend, regardless of the fact that applications have been on an upward trajectory. In June 2017, for instance, while about 3.2 million loan applications were made, only about 1.1 million of loans were disbursed. This representing a 34% success rate.

According to the survey, loan applications and disbursement started declining immediately after the law was signed in August 2016. Loan applications dropped from 2.2 million in August 2016 to 1.9 million in September 2016, a 17% drop. Over the same period, the number of loans that were disbursed fell from about 1.1 million to below 750, 000, a 32% decline, as the market came to terms with the effects of the new law.

In general terms, evidence from the tracked effect of the Banking Act indicates that the objectives of the new law are not being achieved in three ways. Firstly, credit is now more skewed towards secure and short-term market end. Secondly, lenders are becoming very risk sensitive and as such are moving away from household and other economic agents that lack dependable collateral, like small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Thirdly, banks are now more biased towards trade than investments, to the disadvantage of manufacturing and other key economic sectors.

Staff and network rationalisation

The law has also promoted adjustments in the banking industry in the form of staff and network rationalisation. From the surveyed banks, there has been a 1,933 jobs reduction as the number of management and non-management staff reduced from 28,009 employees as at August 2016 to 26,076 employees by June 2017. The number of bank branches have reduced from 1,106 to 1,102. Over the period, banks appear to be relying more on agents with the number of agencies rising from 41, 686 as at August 2016 to 53, 667 outlets as at June 2017.

ALSO SEE: StanChart wants interest rate cap reviewed

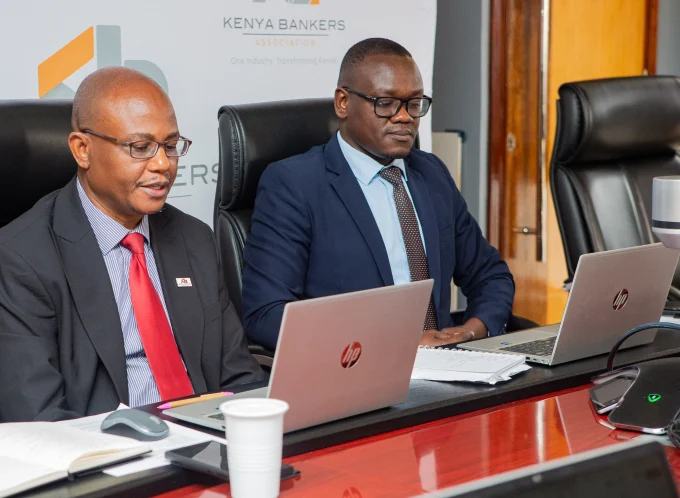

“It is increasingly becoming evident that the expectations of the Act are not being met. The inability for credit to adjust towards meeting the growth slack on the back of weak demand and the link between credit to private sector growth – which is nearly at a grinding halt – means that the greater economy is being hurt,” said Habil Olaka, KBA’s Chief Executive Officer, while releasing the survey results.

The lenders say the survey came up with very scant evidence, if at all, that the law has spurred savings or deposits mobilisation. If anything, the study noted, the law has seen banks put focus on effective management of the cost of funds. Such cost management could be skewing the liabilities (deposits) towards even shorter tenors, the survey notes.

“It is now a high time for all stakeholders including the Treasury, Central Bank and the legislative arm, to re-engage and address the delivery of lower interest rates for the average Kenyan from a win-win standpoint,” added Olaka.

Speaking during the press briefing, Jared Osoro, KBA’s Director of Research and Policy, reiterated that there is an apparent slowing of the appetite of international Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) to extend lines of credit to the banks for the benefit of the private sector. Indeed some of the DFIs are undertaking formal studies to guide their views on new and/or renewal of lines of credit. “While it had become clear that lines of credit were becoming popular amongst Kenyan banks, we are not seeing much enthusiasm in that space”.

The law capping the interest rates that commercial banks charge at four percentage points above the Central Bank Rate (CBR) came into force on September 14 last year. Under the same law, banks have to pay depositors at least 70% t of the CBR.

Leave a comment