Time is not on the side of Africa to make the 21st century the continent’s century for development. Underpinning the pace (or not) of progress is the need to make sound rather than popular policy decisions, and act on them.

By 2050, Africa’s population will double to more than two billion. The vast majority of these people will be under the age of 25 and live in cities. Former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo, with whom I co-authored Making Africa Work, outlined the problem facing the continent perfectly when he said recently:

“Unless there is a major change in the speed of economic development across the continent, we are sitting on a ticking time-bomb.”

It is against this background that the pace and progress of policy development across Africa must be considered. Yet, too often have brave policy decisions been ducked and political self-interest taken precedence at the expense of long-term policies developed for the overall national interest.

Politics and choices matter in dealing with poverty, as Asia shows, and Africa’s record is at best mixed in this regard.

Few countries have seen this more starkly than Zambia, where a desperate government, starved of resources to pay the salaries of an inflated civil service and an inability to meet the international debt obligations it has recklessly rung up in record time, continues to take actions that will inevitably hobble the country’s economic development potential.

In May, the government decided to raid and apply for the liquidation of Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), the country’s biggest PAYE taxpayer through its 13,000 employees. In response, the Zambian opposition leader and economist, Hakainde Hichilema, noted: “In order to share a pie, you must first be able to cook a pie.”

The implication is clear. You cannot improve the lives of the citizens you govern without first having the right ingredients: the basics of sound macro-economic investor-friendly policies, the rule of law, physical security, functioning infrastructure and the software that goes with it, and a critical mass of skills. Decisions have to be guided by a sense of popular welfare, primarily, not the politicians’ priority to duck responsibility and simultaneously fill their pockets.

The Zambian government’s decision to apply to place KCM – in which it is ironically a significant shareholder and on whose board it has three representatives – into provisional liquidation appears to have less to do with a crackdown on the company for a failure of governance, and rather more as a desperate plan to redistribute the company’s assets between Zambia’s increasingly antsy external creditors and politically connected individuals.

The impact of this action is clear to see – widespread job losses at a time when unemployment levels are rocketing, coupled with a loss in tax revenues for the government.

This can only further the vicious cycle of debt and social problems in a country now ranked one of the most unequal countries in the world as the proceeds of growth are redistributed, principally among an apparently careless Lusaka-based elite. The top 10% of Zambians receive 52% of all income, while the bottom 60% of the 16 million population get just 12%.

Kenya crackdown on online betting

Without economic development, there can be no social development. The lessons of history also confirm that the greatest creator of tax revenues and fiscally sustainable jobs is the private sector. Yet, all too frequently across the continent, far from being celebrated for this contribution, private industry is a target of attack.

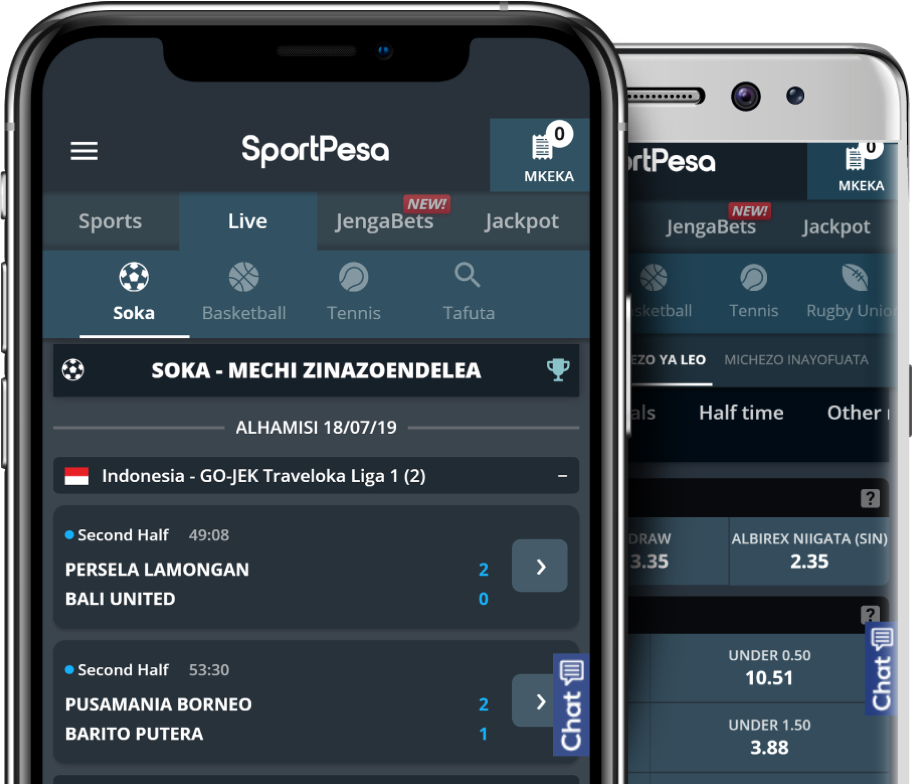

Last month, in Kenya, a similarly disruptive approach was taken by the government on the online betting industry, leading to the two largest companies, among others, being closed with a widespread loss of jobs.

The two had between them contributed a big chunk of tax revenue, some Ksh 10 billion ($100 million) in 2018 alone. Whatever the debate about the ethics of online betting, Kenya, like Zambia, is gaining levels of public debt that are unsustainable and has some of the highest levels of youth unemployment on the continent, while facing continued rapid population growth. Tax revenue is crucial to building an effective state. And the only way to increase revenue sustainably is to grow the private sector.

Such actions have other, wider consequences. The Kenyan football league depends on this income for sponsorship, as do a multitude of grassroots soccer clubs countrywide. Long term, the impact to foreign investor confidence is hardly likely to be positive when local rules change suddenly and apparently arbitrarily.

At a time where every African government should have a laser-like focus on growth, job creation and development to meet the demands of their expanding populations, many are easily distracted by problems of identity and the management of narrow constituencies to the neglect of national issues. In particular, too many are failing to recognise the need to align public sector actions with private sector concerns, and to act on plans, positively and with urgency.

Without such action, and focus, to extend Hakainde Hichilema’s analogy, the pie will not grow fast or big enough to feed Africa’s burgeoning population.

Leave a comment