Journalists and the media fraternity around the world on Monday, May 3, marked World Press Freedom Day. In Kenya, events included a function organized by the Media Council of Kenya (MCK) where Speaker of the National Assembly Justin Muturi was among those who spoke.

Speaker after speaker reflected on this year’s theme of ‘Information as a Public Good’, noting the crucial role the media plays in the country, highlighting strides made over the years and offering solutions to the numerous, sometimes seemingly insurmountable, challenges that define the operations of the media.

Muturi called for better compensation of journalists – citing Purity Mwambia’s hit investigative documentary Silaha Mtaani as evidence of the risks journalists take to deliver impactful stories. He urged members of the press to use all legal and ethical means to keep public officers accountable as they obtain and disseminate information.

Listening to the speeches, the long-held perception of Kenya’s support for media freedom was apparent. The facts, however, tell a different story.

Often, Kenya’s oft-talked-about media freedom has been seen through the lens of stringent regulations effectively gagging media in neighbouring East African countries as well as other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. Unfortunately, on a continent where media markets are vastly under-developed and governments are keen to control the flow of information, the bar for what is considered free media remains low.

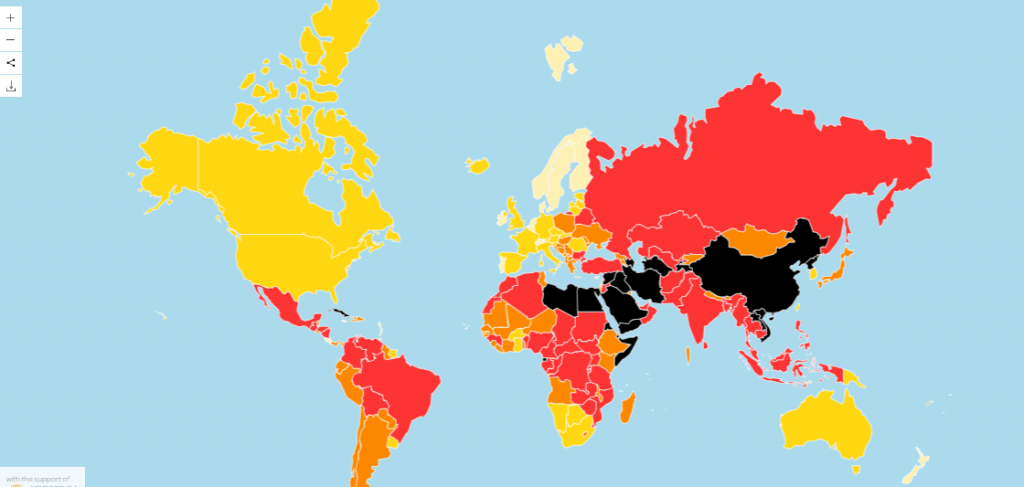

It is time Kenyan journalists, media managers and entrepreneurs asked themselves some tough questions – including why the country has steadily been dropping down Press Freedom rankings in recent years, ranking at 102 out of 180 countries in the 2021 Reporters Without Borders global press freedom index.

On the color-coded map by RSF, Kenya stands out as one of a handful of countries in Africa not in red, which represents dangerously low press freedom levels. It however, ranks way below countries such as South Africa, Namibia and Botswana which ranked 32, 24 and 38 respectively.

As the researchers aptly noted about the media environment in Kenya; “The 2010 constitution guarantees press freedom but respect for this freedom is precarious and depends a great deal on the political and economic environment.”

“Politicians continue to exercise a great deal of influence over both state and privately-owned media, which censor themselves to a significant degree, avoiding subjects that could cause annoyance or might jeopardise income sources. Impunity is the rule. Investigations into violence or abuses against journalists are still very uncommon and, as local NGOs point out, rarely lead to convictions,” the report further observed.

It is time Kenyan media stakeholders ask themselves if the illusion of press freedom is good enough for them, and, if it isn’t, are they ready to do what it takes to get the real thing?

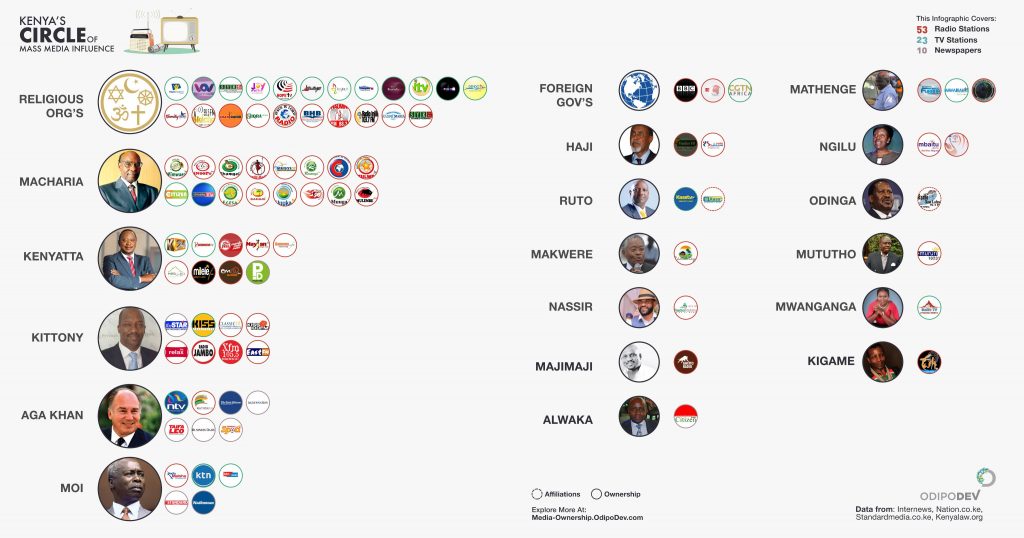

Research by OdipoDev in 2018 revealed the extent to which politicians and individuals with political affiliations dominate the media market in Kenya at the highest levels – owning many of the biggest platforms.

The data revealed that close to 37% of all newspaper, TV and radio entities in Kenya have ownership exposed to proven political influence either directly or indirectly.

While some out there will tell you that Kenyans are obsessed with politics and can’t stop talking about it (one diplomat described it as our national sport), have we considered that the media might be force-feeding the people content driven by the interests of their owners and their associates? Is this happening at the expense of delivering more important, people-centric stories?

It’s not a Kenyan newsroom if you don’t regularly get requests or demands to pull down, or not publish/air at all, stories touching on influential figures, companies and their associates – even when no laws have been broken in obtaining and sharing the information.

Media companies often acquiesce to these demands for various reasons, including out of fear of harassment, intimidation, expensive legal battles and loss of advertising revenue. That journalists and media firms don’t feel protected enough to carry important stories tells a lot about the reality on the ground.

And while legacy media firms can bear the costs of fighting it out with the big boys in court, newer, often digital-native players can easily sink under the weight of court battles.

Last year, NTV aired a stunning investigative documentary, Covid Billionaires, detailing massive corruption in the use of funds allocated by the government to the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite the Auditor General later confirming the looting with a special audit and formal investigations being launched, the documentary had to be pulled down after an individual whose company was mentioned went to court and secured the order.

A big part of the problem has been the mainstream media’s reliance on the government for a large chunk of their advertising revenues – a situation that has left journalists and editors at the mercies of higher-ups. Having seen the error of their ways, many of the media houses have began implementing strategies to boost reader and non-governmental advertising revenue.

Players in digital media who have shaken up the industry remain an important part of the eco-system, but also have to take up the challenge to respond to the evolving needs of audiences.

It is time to give media consumers more value than ever – by telling truly bold, exciting and impactful stories and redefining expectations of Kenyan media production.

It is also time to take on threats to press freedom head-on, and demand that bodies including the Media Council of Kenya (MCK) remain truly independent as envisaged by the 2010 Constitution.

Leave a comment