Why do Kenyan businesses seem so badly managed? What can be done about it? These two questions linger in every person’s mind, especially when you hear that a business that you thought was thriving is tumbling.

Of course the malaise is not confined to Kenya, as the past few years of global recession have demonstrated. But since we’ve refused to join the recession, my theory is that we’re not obliged to follow anyone else’s lead to do a whole lot better. If we can’t find many role models of excellence, let’s create our own.

As a somewhat long-in-the-tooth business consultant, I have something of a unique perspective on the inside of business management across multiple sectors. I’ve seen CEOs and their management teams come and go, change programmes fizzle out and strategy reports collect dust on the shelf. It’s part of our profession to try to understand why this is so, and to dream up solutions.

Frequently we sit together as a team, sometimes with our business partners and clients, often around a bottle of wine, in an effort to do this. And here’s what we’ve concluded: mediocrity is rife, and it’s driven by complacency, laziness and incompetence.

The flashes of excellence which do occur are quickly stamped out before they catch hold.

Feel free to argue! But I hope we’ll be able to marshall enough evidence not just to convince you but to shake Kenya’s business leaders out of their collective comfort zones. If anyone wants to do things better, it should be really easy – because no-one else is doing it.

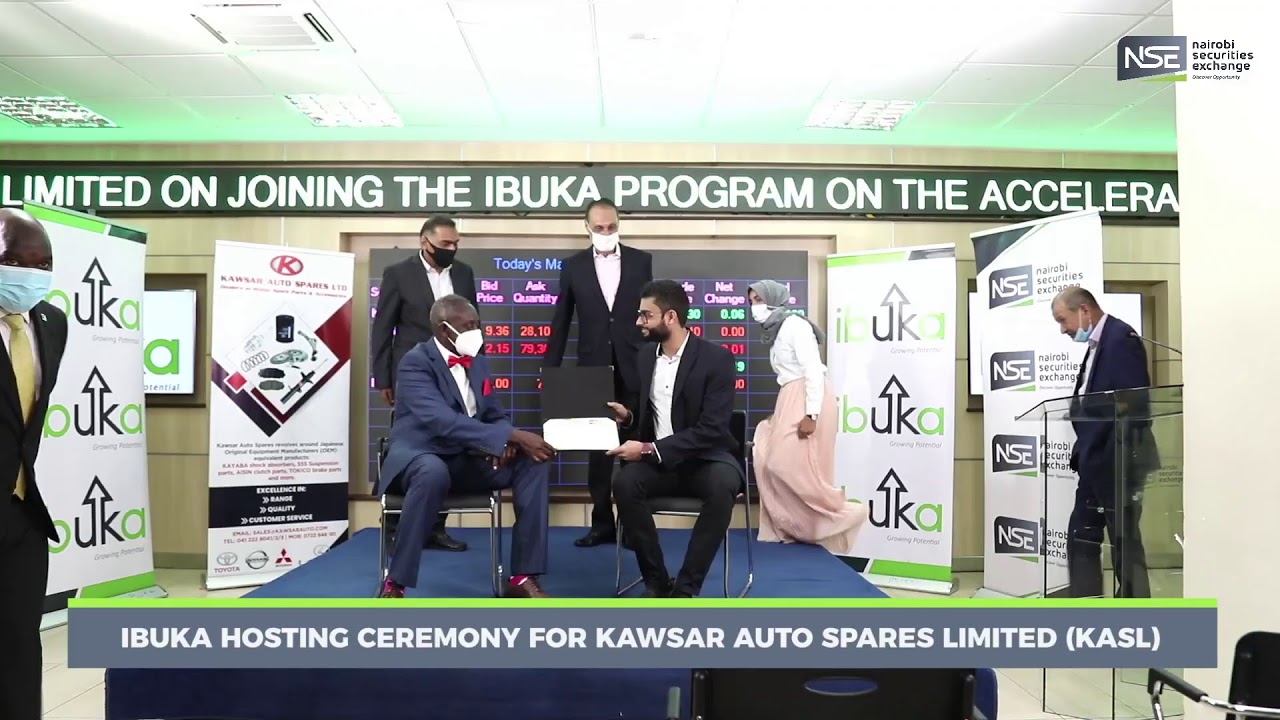

Here’s my first bit of evidence. The Nairobi Stock Exchange 20 Share Index stands (June 2012) at 3653. Let me not claim this is fully indicative of the state of the entire economy, but that’s LESS than it was in 2005 by about 8%.

In other words, something like six billion dollars has been lost in value from these companies over that time. Now, considering that it’s the directors’ job to protect and enhance shareholder value, what does this tell us?

Yes, I know voices will be raised claiming you can prove anything by a judicious use of statistics. And that stock prices worldwide have been in the doldrums for some years. And that NSE figures seem to shift according to when and where they are published.

But no-one can rightly claim that the market value of Kenya’s publicly quoted companies is at a high. In fact the pattern of rise and fall suggests that sentiment – particularly post-election confidence – more strongly influences performance than does the actual business of managing the company.

Share value is not the only indicator of performance, though it’s an important one. But profitability has also not been as good as it could be. Neither has growth. I talked to a CEO who told me that his Chairman asked him specifically not to make a profit on the grounds that it would simply go to KRA.

Perhaps they embrace what people sometimes call a ‘tax-loss’. But whatever you call it, it’s still a loss. And companies shouldn’t be run in order to make losses, or am I missing something?

It would be bad enough if this was a privately held corporation, owned by people who had already made their pile. But it was a publicly quoted company whose minority shareholders are simply being cheated. I challenged another board on their seemingly unambitious growth targets.

Ten or twelve percent was what they put into their strategy document. But in a high inflation economy – which we still are – that’s not growth, it’s contraction. To be meaningful, growth needs to be in excess of 20 or even 30%. And there are companies around who are achieving that.

Why would a company not want to grow? Yes I know there are risks in raising your corporate profile above the parapet, but there are surely equal and opposite risks in staying small.

Against this kind of backdrop, my qualitative conclusion is that CEOs and their teams are reluctant to stand up to their boards. And that those boards are often stuffed with people whose vision can only be described as myopic.

Management teams are also often reluctant, if not positively resistant, to making decisions in the best interests of their companies, their shareholders, their long suffering customers and their bemused employees.

Perhaps there is little to be gained by swimming against the tide, while there may, in reality, be a great deal to lose. After all, the pay cheque comes in every month regardless, so why rock the boat that carries the golden goose, if I may mix my metaphors?

School fees and mortgage payments take on a higher priority than does corporate competitiveness. Worldwide, the sector that has come in for the most criticism for its complacency and incompetence is banking. In our neck of the woods, such talk has been muted.

Which is a pity, because our own bankers are as complacent as any. Why else would there be such an enormous spread between lending and deposit rates, for example?

There is no incentive to tighten ship and run an efficient organisation. Profits are made willy nilly, as much as anything because banks can levy fees and commissions on their customers without even informing them, let alone negotiating competitively.

Banking is quite literally a licence to help yourself to your customers’ money. No-one talks much either about the rampant fraud and theft which is going on.

When bank employees creatively siphon off their customer’s cash, they tend to be quietly fired in an attempt to avoid the limelight, soon to pop up in another position at another bank.

Banks’ management teams appear to lack the courage or the incentive to admit to the scale of the problem, and they massage the losses between their excessive rate spread.

(This article has been published in the Nairobi Business Monthly, July 2012 Edition)

![Pula Co-Founders and Co-CEOs, Rose Goslinga & Thomas Njeru. Pula provides agricultural insurance and digital products to help smallholder farmers manage climate risks, improve farming practices and increase their incomes. [ Photo / Courtesy ]](https://businesstoday.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Pula-Co-Founders-and-Co-CEOs-Thomas-Njeru-Rose-Goslinga.jpg)

Leave a comment