Kenya has been ranked as partly free in the Freedom in the World 2018 report released by Washington-based watchdog, Freedom House.

The country scored a 4/7 in freedom rating, political rights and civil societies where 1 represents most free and 7 least free. The country’s aggregate score stands at 43/100 where 0 represents most free and 100 least free.

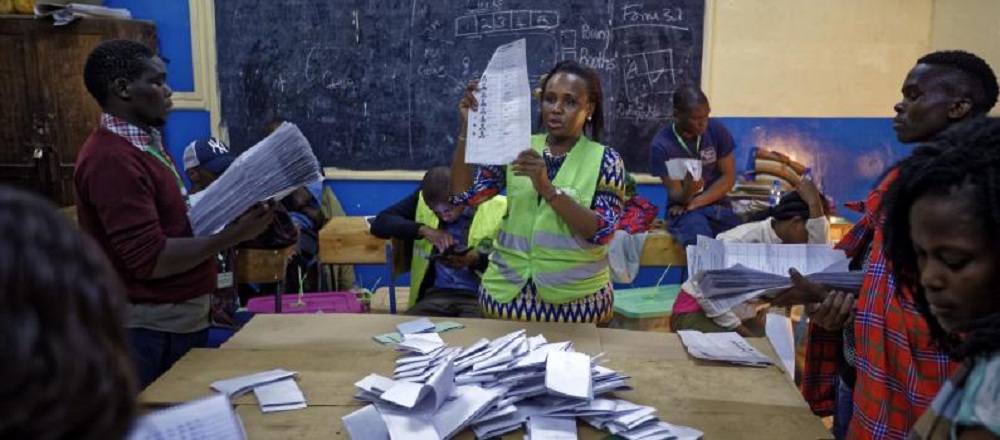

While a full report on the country’s performance is not yet available online, a summary of the report notes that a deeply flawed electoral process in Kenya last year contributed to political violence in the country.

“Kenya’s Supreme Court initially won broad praise for annulling the results of what it deemed to be a flawed presidential election. However, the period before the court-mandated rerun was marred by a lack of substantive reforms, incidents of political violence, and a boycott by the main opposition candidate, Raila Odinga. These factors undermined the credibility of President Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory, in which he claimed 98 percent of the vote amid low turnout,” the report reads.

According to the report, political rights and civil liberties around the world deteriorated to their lowest point in more than a decade in 2017, extending a period characterised by emboldened autocrats, beleaguered democracies, and the United States’ withdrawal from its leadership role in the global struggle for human freedom.

“Democracy is in crisis. The values it embodies—particularly the right to choose leaders in free and fair elections, freedom of the press, and the rule of law—are under assault and in retreat globally. A quarter-century ago, at the end of the Cold War, it appeared that totalitarianism had at last been vanquished and liberal democracy had won the great ideological battle of the 20th century,” says Michael J. Abramowitz, the Freedom House President.

“Today, it is democracy that finds itself battered and weakened. For the 12th consecutive year, according to Freedom in the World, countries that suffered democratic setbacks outnumbered those that registered gains. States that a decade ago seemed like promising success stories—Turkey and Hungary, for example—are sliding into authoritarian rule,” he adds.

Closer home, he notes that in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi, incumbent rulers’ ongoing use of violence to flout term limits helped to generate internal displacement and refugees.

In neighboring Tanzania, the government of President John Magufuli—who took office in 2015 as a member of the only ruling party the country has ever known—stepped up repression of dissent, detaining opposition politicians, shuttering media outlets, and arresting citizens for posting critical views on social media. And in Uganda, 73-year-old president Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986, sought to remove the presidential age limit of 75, which would permit him to run again in 2021. Museveni had just won reelection the previous year in a process that featured police violence, internet shutdowns, and treason charges against his main challenger, Abramowitz says.

Even in South Africa, a relatively strong democratic performer, he notes that the corrosive effect of perpetual incumbency on leaders and parties was apparent. A major corruption scandal continued to plague President Jacob Zuma, with additional revelations about the wealthy Gupta family’s vast influence over his government. The story was expected to play a role in the ruling African National Congress’s December leadership election, a contest between Zuma’s ex-wife and ally, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, and Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa.

READ: KTN replaces Carol Nderi in bureaus reshuffle

According to the Freedom House President, the process by which elected president Robert Mugabe was compelled to resign in November under pressure from the military pushed Zimbabwe over the threshold from Partly Free to Not Free in Freedom in the World 2018. This downgrade may seem counterintuitive given Mugabe’s long and often harsh rule, the sudden termination of which prompted celebration in the streets. But it was the regime’s years of repression of the opposition, the media, and civil society, and its high levels of corruption and disregard for the rule of law, that placed Zimbabwe at the tipping point between Not Free and Partly Free prior to 2017.

He says the next year will be crucial for Zimbabwe, as general elections are expected. It remains to be seen whether newly installed president Emmerson Mnangagwa—a stalwart of the ruling party—is prepared make much-needed reforms that would enable free elections, or will simply retain the uneven playing field that had allowed Mugabe to remain in power since 1980.

I would like to see USA reports as well, in the onset of trump gagging the media openly and insulting opponents and interfering openly with collusion evidence.