Nairobi-Kenya

Radio is a peculiar animal – not quite the dinosaur it was predicted to be before the rise of social networks such as Facebook and Twitter. It is an eccentric institution, constantly changing, but never managing to camouflages its sharp edges to blend in with the surrounding.

These days, radio that brings in gossip is bound to flourish than the one that rigidly sticks to BBC-style bulletins, because customer is king and advertisers follow the numbers.

This explains why international stations in Kenya, namely British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Voice of America, Radio France Internationale, Radio Netherlands Worldwide, Channel Africa, DeutschVelle Radio, China International Radio and many others, are desperately struggling to survive.

These stalwarts of media have steadily lost audience to a new crop of local FM channels, some utterly unethical, established after the airwaves were liberalised in the 1990s. Since then, radio has been forced to adapt to the audience’s tastes and trends, even at the cost of the cardinal customs that demanded the audience to be respected, not patronised.

“Radio is very local,” says Communications consultant Michael Otieno, who is the general manager of Hill & Knowlton Strategies. “It has evolved from being a channel for transmitting news and information from a central source which was mostly the know-it-all government to being a medium where we can talk about issues happening in the neighbourhood. It’s our verbal gossip column where we talk about who is sleeping with who, we talk about our most intimate issues, fears and eccentricities. To sum it up crudely, morning and afternoon radio is where the nation comes together for group therapy.”

Most international radio channels are government-funded and thus managed by rigid bureaucrats and managers who have an editorial brief that does not necessarily resonate with the local conditions.

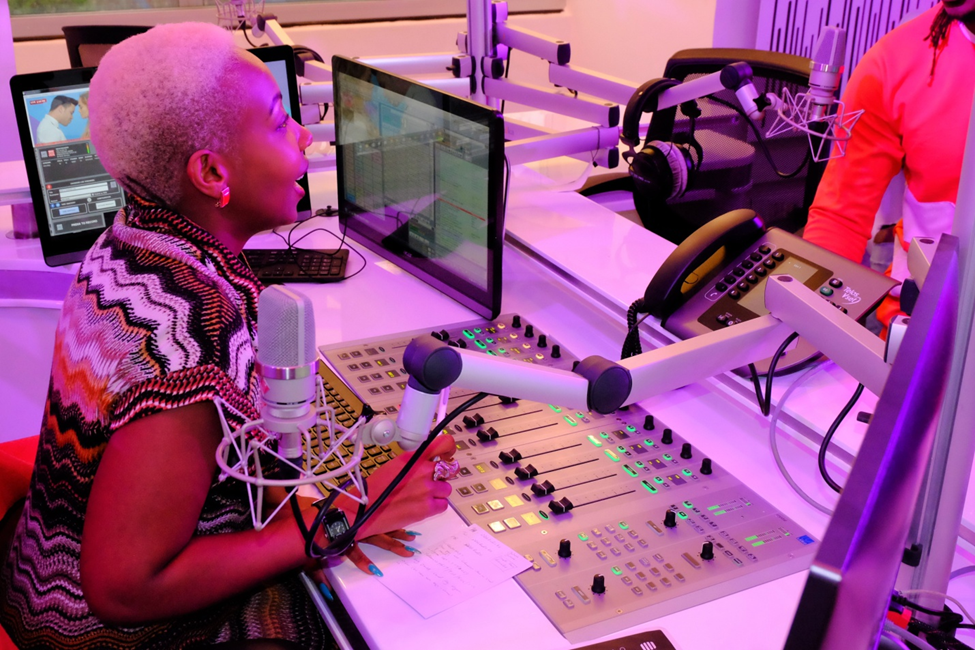

Local stations, on the other hand, are headed by creative and entrepreneurial minds driven by the profit motive and displaying eccentric tendencies only tolerated as long as they do not spook advertisers. This has seen the rise of maddening presenters like KISS FM’s Caroline Mutoko, Classic FM’s Maina Kageni and Ciku Muiruri and Capital FM’s Cess Mutungi, who have been key players in breaking the old rules.

Mr Otieno, who is a fan of Classic 105, KISS FM and Capital, adds: “What would you rather listen to while held up in traffic on Mombasa Road, a channel that is telling you about a shooting in Denver Colorado, or about your local priest busted with the holier-than-thou choir girl?

This is not to trivialise international incidents, but the international news must be so compelling, for example, the historic election of Obama as the president if the United States for it to compete with local news about the latest antiques of Mike Sonko, gossip and trivia.

” In local FM radio, themes and stories abound that can not be allowed in BBC or any other international radio station where the rules are rigid, programming is subjected to tough academic standards, journalism is practised according to the rules of accuracy and the audience is often respected.

In radio shows, for example, the line between fact and opinion has been blurred. Last year, several lewd SMS messages that were sent by members of the public to Classic FM radio during its popular interactive sessions were leaked and dumped on internet, exposing private mobile numbers.

It sparked a firestorm, prompting the Media Council of Kenya to issue threats, but which instead made the show more popular. And a few years ago, Radio Africa Group maverick chief Patrick Quarcoo allowed Classic FM’s sister channel, KISS FM, to dupe the media that Ms Caroline Mutoko, star presenter and marketing manager, had been kidnapped. International news agencies like Reuters wrote the story only to realise that it was a victim of a plot to market the then infant in on Kenyan radio scene.

“Such stunts would not have been approved at the BBC,” said a BBC journalist who talked to us on condition of anonymity. “But let us face it, Classic FM and KISS FM got their numbers.”

Audience friendly content has also helped local FM radios because programme mangers are working with a defined audience and thus can package content to match the market demands, unlike international channels where it could take several years to effect changes.

Recently, BBC World Service Radio merged long running Network Africa and World Today, to created Newsday, a breakfast show for African audience. The giant broadcaster agrees that the African audience has evolved tremendously, and thus the need to respond to their desires.

“The BBC across languages and platforms is the biggest international broadcaster to Africa; one-in-two listeners to the World Service in English are in Africa. It’s also one of the most rapidly changing media markets,” said Mr Andrew Whitehead, the Editor of BBC World Service News.

He added: “Newsday is about bringing the world to Africa, and bringing Africa to the world – an exciting team of presenters, with a fresh sound and style to engage with Africa’s very large radio audience at breakfast time. And our goal: we expect Newsday to be the most listened to radio news programme by an international broadcaster. It will certainly have more listeners than any other BBC radio news programme.”

To bridge the gap, international channels have launched partnership with Kenyan radio stations to broadcast their programmes and shows in a desperate bid to expend their numbers. Radio Netherlands World, Voice of America and Deutsche Welle Radio have partnerships with Kenya’s elite radio, Capital FM. Over the years, the BBC radio has partnered with several local radio stations, allowing them to broadcast its programmes, mainly news.

“If you cannot beat them, join them,” said Josephat Mwangi, a media expert in Nairobi. Even before radio, the BBC surveyed its market and understood that its consumers in Africa wanted news packaged in an African way, thus the birth BBC Focus on Africa TV, another attempt to remain relevant.

“While radio remains popular in Africa, TV is growing – and our partnerships with leading African broadcasters play a key part in these future plans. Mobile phone ownership is racing towards the one billion mark, internet connectivity is rising and social media is empowering audiences. It’s essential that the kind of independent journalism the BBC does that isn’t slanted to one political or commercial viewpoint remains central to the new media landscape,” said BBC Africa Editor Solomon Mugera.

With correspondents in 48 African countries, production centres in Nairobi, Abuja, Johannesburg and Dakar and a weekly audience of 77 million, he said, the BBC already has deep roots in the continent. “Our journalists are from the African countries they report on – in English, Swahili, Hausa, Somali, Kinyarwanda/Kirundi and French – living and breathing the big stories and issues facing Africa,” Mr Mugera added.

According to Torin Douglas, the BBC media correspondent, the broadcaster is explicitly reducing its commitment to some audiences and urging them to switch to its commercial competitors, an indication that is now ready to fight in the trenches for its survival since the government has hinted at slashing funding.

The BBC has had to change because, according to journalist Derrick Buliva, taste, fashion, style and popular culture, public opinion and social attitudes are permanently on the move, and so is news.

“Do you think a Kenyan in some backwater village will give a damn about Barclays PLC manipulating interest rates or some foreclosures in Kansas? A Kenyan will tune in to a radio station that addresses issues of his or her immediate needs,” he explains. With BBC, the pioneer and most successful giant, taking such radical steps, the rest are likely to follow the trail.

Content is king and will always drive the audience, says Mr Jared Obuya, a former BBC journalist and current Kenya Union of Journalists’ secretary general. Media experts have argued that so-called “relevance” has driven many editors and producers crazy, compelling them to package programmes and bulletins based on consumer value and appeal rather than significance.

The biggest segment of audience in Kenya is Swahili and vernacular listeners, who are more fascinated by interactive phone-in programmes, discussing topical issues, music and some carefully chosen news segments.

That is why Royal Media Services (RMS), which runs at least 14 radio stations, including 12 vernacular channels, controls 34% of the radio market, Kenya Broadcasting Corporation 18%, Radio Africa Group and Nation Media Group controls about 6% each, according audit firm Deloitte in a study called “Competition Study – the Broadcasting Industry in Kenya”.

When the government liberated the media in the 1990s, newly established FM stations started offering competition to KBC, which had ceded ground because it could be easily be manipulated and international channels – mainly BBC, DW Radio and VOA – were the only source of unbiased news.

This liberalisation came with political pluralism, which allowed the newly created entities to position themselves as the alternative source of news. This forced KBC radios to start shedding their gothic past as the radio market was cut to several bite-size business-friendly niches. As it remodelled and streamlined to suit the new consumer tastes amid competition from the FMs, the biggest loser were the giant radios, unable to change and adapt faster because of the state bureaucracy and sheer size.

The competition for numbers got dizzying when many phones came with FM receivers, increasing the audience 10-fold. Nobody would tune in to the hourly BBC or VOA hourly news bullets when a local FM presenter, in a brief interlude, updates the latest international news, gossip and anything that would be happening.

Now, even local FM radio stations Twitter and Facebook pages where they update news and engage debate. According to a 2010 study, “The Media We Want: The Kenyan Media Vulnerability Study”, by Peter Oriare, Rosemary Okello-Orlale and Wilson Ugangu, radio remains the leading media in Kenya, with the audience preferring vernacular stations as opposed to English, Swahili or French, languages preferred by international radios.

“Kenya’s audiences can access diverse media choices but they are heavily fragmented. Audience habits, preferences and patterns affect media behaviour. Kenya’s media consumers use radio the most, followed by television and newspapers. They expose themselves to more than one channel and media per day,” they said.

That was 2010, now the numbers are higher. “Kenyans have adapted to mobile telephony quickly as manifested by their use of mobile-phone banking such as M-PESA, but many still prefer ethnic language media to English and Kiswahili radio stations. They demand media loyalty and ignore media that are unable to satisfy their unique political susceptibilities and sensitivities.

Audiences in Kenya change quickly, forcing the media to adapt to their needs and interests promptly. Although media literacy is low, trust in the media to report accurately on political issues is very high,” the report added.

The largest share of the country’s at least Sh65 billion advertising revenue is consumed by local commercial radios, giving them the much-needed muscle to wrestle audience from their international rivals by offering promotional freebies such as mobile phones, airtime, free lunches, holiday trips and even cash rewards. Unfortunately, BBC, VOA and other channels cannot match that. “Media revenue from advertising has steadily grown since 2003; and is consistent with the growth of additional segments of the media.

Although the government – easily the largest spender in the Kenyan economy – has a tendency to punish independent and critical media through denial of advertising, other private advertisers use their financial muscle to have their way with the media on sensitive matters that touch on them,” the study found out.

State-subsidised international broadcasters understand and respect the principles of advertising, and therefore find it hard to compete with the locals which target a defined audience segment.

For example, a vernacular radio targeting only one tribe can momentarily adjust to meet market demands, unlike the BBC targeting all Swahili speakers in East and Central Africa or English speakers across Africa to adjust effectively and suite the audience tastes and expectations because its coverage zone is too big.

“An advertising code is in place, but adherence is weak,” according to the study. “Advertisers in the tobacco and alcohol industry use mediated corporate social responsibilities strategies to bridge the gap created by anti-tobacco and alcohol advertisement laws.

Some big advertisers and sponsors pay journalists and editors to guarantee positive coverage.” This advertising headache is an international phenomenon. Last year, KBC irked its reggae fans when it shut down its loss-making Metro FM and created Venus FM in a bid to boost its revenues.

BBC, the portrait of successful radio, has been reducing its vernacular language stations across the world to save funds to boost its flagship BBC Worldwide.

![Pula Co-Founders and Co-CEOs, Rose Goslinga & Thomas Njeru. Pula provides agricultural insurance and digital products to help smallholder farmers manage climate risks, improve farming practices and increase their incomes. [ Photo / Courtesy ]](https://businesstoday.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Pula-Co-Founders-and-Co-CEOs-Thomas-Njeru-Rose-Goslinga.jpg)

Leave a comment